| Peace and Environment News * July-August 1995 |

Landmines: a Modern Scourge Waiting to be Banned

by Evelyn Henderson

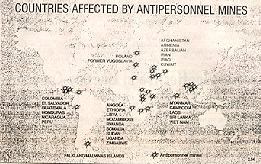

Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Peru, Poland, Former Yugoslavia, Angola, Ethiopia, Libya, Mozambique, Rwanda, Somalia, Sudan, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Falkland/Malvinas islands, Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, Sri Lanka, Viet Nam. |

Anti-personnel mines come in many sizes, shapes and colours, some with trip-wires, some made of metal, and others almost all plastic. They lie hidden, sometimes for decades, ready to explode when stepped on or snagged by unwary victims.

Hundreds of thousands of people have been killed or maimed by landmines in the last twenty years. Cambodia is a prime example. During its long civil war more people were killed by mines than by any other weapon. One out of every 236 Cambodians is an amputee—there are 300-400 amputations a month—and the toll keeps rising.

Mine clearance is very slow, dangerous and costly work. In the words of a U.S. prosthetist, "Cambodia is being demined an arm and a leg at a time." Producing a landmine can cost as little as $3; deactivating it as much as $1,000. Every year some 85,000 mines are cleared, and 2.5 million new mines are laid. Plastic mines are not detectable.

The military establishment claims that mines are an indispensable defensive weapon in time of war, but there is no doubt that many are targeted against the civilian population. Some governments are prepared to continue using them despite the suffering of innocent people. The horrors of death and mutilation are only compounded by the longterm effects of landmines on the environment. Mined agricultural land is too dangerous to till, and people's ability to grow food for themselves has been wiped out.

The language used to describe landmines indicates a depth of revulsion hard to equal: atrocious, insidious, indiscriminate, pernicious, inhumane, uncontrollable, deadly, silent killers.

Since the mid-1880s, the international community has made efforts to establish international humanitarian laws, codifying them in Conventions, drafted for the most part in Geneva, Switzerland. These conventions are binding on countries that sign and ratify them. A United Nations Conference in 1980 led to the Inhumane Weapons Convention dealing specifically with landmines. Unfortunately some of the provisions are unrealistic and virtually unworkable, "full of holes and weaknesses." However, a Review Conference is planned for September, 1995 in Vienna. Canada ratified the Inhumane Weapons Convention in June 1994, and has taken part in four meetings of an Experts Group preparing for the Review.

An International Campaign to Ban Landmines has been formed, which works on the premise that no control measures will ultimately eliminate the scourge of landmines—a total ban is the only way to go. To support this initiative, a wide range of Canadian non-governmental organizations have formed a coalition called Mines Action Canada (MAC). In Ottawa, MAC is coordinated by Physicians for Global Survival. MAC represents a bold and positive approach to assisting civilians in mined areas, most of which are in developing countries with very limited resources.

Mines Action Canada has set out the following four objectives, which it is calling upon the Canadian Government to endorse and implement:

1. The Canadian Government should call for a total ban on the use, production, stockpiling, sale, transfer, or export of anti-personnel landmines;

2. An immediate Canadian moratorium should be placed on the production and export of landmines, their component parts and related technology;

3. Supports Canadian, multilateral and local humanitarian mine clearance initiatives;

4. The Canadian government should increase assistance for victims of landmines.

On March 2, 1995, Belgium became the first country in the world to pass legislation to ban landmines, their production, procurement, sale or transfer, including parts and technology. The vote in Belgium's Parliament was unanimous, and by acting unilaterally, Belgium has set a precedent, risking criticism from other NATO countries.

Here in Canada, Svend Robinson, M.P. for Burnaby-Kingsway, tabled a Motion this March on the Order Paper of the House of Commons, related to landmines in the four areas of: international law, unilateral moratorium on production and export, mine clearance, and support of mine victims. This was added to a pool of motions, and its chances of being drawn for debate in the House are slim, but it is heartening to have it tabled. Other M.P.s have raised the landmines issue in Parliament. Readers are invited to contact their M.P. and urge overt support for initiatives leading to a total ban on landmines.

The hope of the International Campaign to Ban Landmines, in the long term, is to persuade governments around the world to halt their sometimes clandestine production and trade of landmines, estimated at 5 to 10 million annually. There must be a swing to what will become a strong public and professional taboo against landmines. As Patrick Blagden, a U.N. demining expert, has said, "Until there is complete rejection of the use of antipersonnel mines, just as there is for chemical and nuclear weapons, the ban won't get very far."

This poses a challenge we cannot ignore.

Resources

Videos: "A Deadly Harvest" (30 minutes); "A Footstep Away" (three half-hour segments); call Ploughshares Ottawa (Ruth Loomer), 727-8255, or PERC, 230-4590.

Publications: "Landmines: Time For Action—International Humanitarian Law" (from the International Committee of the Red Cross);

"Landmines: Seeds of death across the globe" (from the U.N. Department of Humanitarian Affairs);

"Antipersonnel Landmines: a scourge on children" (from UNICEF).

Evelyn Henderson is a member of Ploughshares Ottawa.

Converted August 22, 2000 - Lg

To follow up on this article, contact the author or the organizations/individuals mentioned; do not contact the Peace and Environment Resource Centre - we cannot provide follow up or contact information. This article is an archival copy of the printed one in the Peace and Environment News (PEN). Viewpoints expressed should not be taken to represent the opinions of the Peace and Environment Resource Centre, the PEN, or our supporters.